It is never too late for creativity. While writing “a Different Type of Bombshell, The Tin Hats’ Journey through World War II, I began a correspondence and friendship with Paul Donnellan, the English-born son of one of the members of this Canadian military entertainment unit. Inspired by my research into my father’s experience as a Tin Hat, Paul decided, at the age of 77, to continue the story in his own voice. He writes about the search for his father and what it has meant to him and his family. With his permission, I am very proud to share his first article.

Now where exactly should I start this story? Let me begin by saying that at the age of 76 I never knew who my father was and to be realistic I never believed in my wildest dreams that that question would ever be answered.

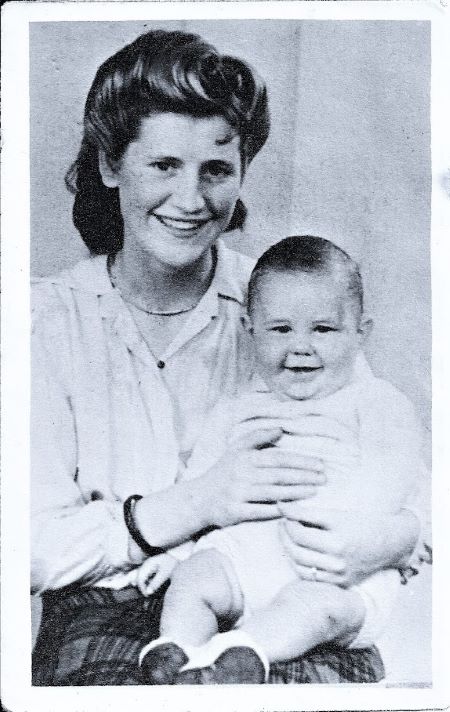

I was born on the 18th November, 1943 on the Isle of Wight into a very large and loving working class family. In those days it would have been very difficult indeed for such a young single mother, as indeed my mother was, to keep and raise a baby. It was so often the case that young girls ‘in trouble’ were sent away to hide that fact and their babies were taken from them. This cruel practice was with us in this country well into the 1970s and the consequences are still being felt to this very day. I was lucky in having a determined young mother and there was no way that she or my grandparents would ever dream of having me adopted. This was war time Britain, the social pressures in so many ways must have made life very difficult indeed but keep me they did.

A Dad at last.

Eight years later, and following a failed marriage in which my mother divorced her husband, my mother married a soldier stationed on the Island at Albany Barracks, Sgt. William Edmund Donnellan of the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers (REME) and for the first time in my life my brother David and I had a dad! We took to him immediately and he to us and we both loved him to bits. From that day we used his name and were happy to do so. Before we knew it Dad had been posted to Libya and we joined him in that exciting and lovely (in those days!) desert and Mediterranean country so far from the Isle of Wight. That was the first of so many moves for those two Army ‘Brats’ and by the time I left school at the age of sixteen I had fourteen changes of school under my belt. It still surprises me that I can read and write. My ‘new’ dad was a veteran of Dunkirk and D Day and served in the Far East. He never mentioned it to us and that is something that I bitterly regret for I should have asked. Did it damage him? The answer to that is yes, it most certainly did. With Dad the family went on to include John, Maria, Peter and finally Michael.

Leaving home and the start of my police career.

Having had enough of so many changes of school, some of which lasted only a fortnight or so, at the age of sixteen I decided that I wanted to join the police; don’t ask why. I wrote to various Forces in the country and was eventually accepted as a Police Cadet by Bedfordshire Police. So, at the tender age of sixteen I left home and found myself living in lodgings at Leighton Buzzard where I was stationed.

Although I was more than happy there, on £5.10s a week I really couldn’t pay for lodgings and other living expenses and go home to Bordon, Hampshire once a month so after only a year I applied for a transfer to become a cadet with the Portsmouth City Police and having been accepted by them it was off to Portsmouth. I loved my time in Portsmouth and to this very day I still regard myself as a ‘Portsmouth City’ man amongst my retired colleagues in spite of the majority of my service having been with Hampshire Constabulary; old loyalties die hard.

No. 6 District Police Training Centre, Sandgate and Shorncliffe Barracks

In September, 1962 I was packed off to No. 6 District Police Training Centre at

Sandgate in Kent to commence three months’ training. I was still a cadet at that time

as it was the policy of Portsmouth City Police to send us there as cadets so instead of having to pay us £9 per week as constables they could save £3 a week by paying us at the cadet rate of £6 per week! That saving of £36 spread out over 30 years’ service works out at £1.20 per annum- what a bargain we were.

I attended the District Training Centre with two other 18 year old Portsmouth City Police Cadets, as well as two other recruits from Portsmouth. The cadets were John Andrews (PC395) and David Burgess (PC394) and the other recruits were PC 362 ‘Bob Gouldie and PC 392 ‘Bob’ Allen. John, David and I are still the very best of friends after more than sixty years.

From Cadet to Police Constable 393, marriage and the death of Dad.

To cut a long story short, on the 24th November, 1962 I took an Oath to Her Majesty the Queen before of a magistrate and became Police Constable 393 of the Portsmouth City Police. I later met and married Cheryl in Portsmouth on 1st October, 1966. Only a matter of weeks’ after our marriage my dear dad died in tragic circumstances.

This tragic event left my mother with four children still at school and Cheryl and I thought it only right that we should be with my family to help and assist in any way we could. I applied for a transfer to the Island and that was granted. My mother was always a very resolute and determined person and now she faced bringing the family up alone. She had a mortgage to pay and she was very determined to make sure that the family stayed in their home. As a result she had to take a job, any job, to pay that mortgage and so she took a job at the bus station in Newport cleaning the canteen and toilets. This job had to be done in the late evening and she would not finish until after the buses had stopped running and so after looking after the children all day she found herself working all the evening and walking the two miles home at gone 11 o’clock at night in all weathers. To this day I really cannot imagine how she managed it but manage it she did for when needs must the devil drives.

I am a great believer that everything in life is relative and that everyone has their Finest Hour no matter how ‘insignificant’ that Finest Hour might seem in the great scheme of things. This was my mother’s Finest Hour for through her efforts she kept the family home and saw all of her children through their education. Was I proud of my mother? I think you can guess the answer to that. My mother passed away on the 21st April, 2022 in her own home aged 94, still as determined and independent as ever. Mum eventually told me that she had tried so hard to inform Bliss (she knew him as ‘Herb’) of my birth but her letters were returned with the word ‘Deceased’ written across them.

As for me, I progressed through the ranks leaving the Hampshire Constabulary as a superintendent in December 1993 having been the superintendent of Southampton Central for six very busy years.

During the two years’ Probationary Period with Portsmouth City Police we were, as already stated, sent to the Training Centre at Sandgate, Kent. During that period some of us were also sent to Shorncliffe Barracks, a short distance away, for our Intermediate Course. How could I have ever have guessed that in sixty years’ time Shorncliffe would play such an important part in my life and in the lives of my family.

The ‘hole’ in my life and the increasing need to know who I am.

Cheryl and I have three children, Lisa, Stephen and Rachel and three grandchildren, of whom we are very proud and although we have a very secure and loving family there was always something missing in my life and that was simply the fact that I had no idea who my father was. Something that had never really bothered me very much when my step-father ‘Don’ was alive now became more important. No doubt that was because I always regarded him simply as ‘my Dad’ and never as a step-father.

As the years passed this became more and more of an ‘uncomfortable’ feeling within me for there was a hole in my life which I felt was never to be filled. The fact that I was acutely aware that my children did not know who their paternal grandfather was did not help and with the arrival of our grandchildren this bothered me even more. No matter how I approached the subject with my mother I could never get any information from her. She obviously did not want to tell me who my father was, the circumstances of their relationship and so that was the end of the matter: I had bit the proverbial brick wall.

DNA. Can this really answer the questions?

As our children grew up it will come as no surprise to learn that they also wanted to know who my father, their grandfather was but as much as I wanted I could not answer their questions but then came DNA.

To say that I was reluctant to go down the DNA route is to put it mildly but having two very bright and, I have to say, persistent daughters meant that this was going to happen sooner than later and happen it did.

Let me say, in my own defence that I thought that the chances of someone having taken a DNA test who was related to my unknown father would be quite remote. The Biblical saying, ‘O ye, of little faith’ now seems to be a rather appropriate. Out of interest it is worth noting that I now have over one thousand DNA connections on Ancestry.com. How wrong can one be?

Eventually and having done as I was told by my ‘pushy’ daughters I duly took the Ancestry DNA test and sent it off. Six long weeks later the result arrived and I found that I had a female cousin in Canada by the name of Geneva. I tried contacting Geneva by email but received no response. My immediate reaction was that she did not wish to get involved with this stranger but in truth she was not checking her Ancestry website and we were to make contact some time later. The rather satisfying proof that the DNA test was accurate came with the results showing that one of my cousins, Ann from the Isle of Wight and her daughter, Jane, were at the top of that very short list.

In the meantime and armed with Geneva’s details my daughters started their own search. In no time at all, or so it seemed, Rachel had traced my ‘new’ Canadian family right back to 1762 to a young Scotsman by the name of Alexander Fraser MacDonald from Ardnamurchan in Argyllshire. He had left Scotland for North America at the age of fifteen, joined the British Army and fought in the American Revolutionary War, surrendered with the MacDonald Militia at Yorktown, went to Canada and settled on the banks of the Miramichi River in New Brunswick. He became a well known business figure, a land owner and the officer in charge of the local militia. His farm, MacDonald’s Farm, is still there and is an Historic Visitor Centre.

Rachel finds my father – The Joy and the Sadness

Having established all this and drawn up a very full and impressive family tree Rachel came to me, pointed out a name and said, with great confidence, ‘There is your father.’ The name that she pointed out was Herbert Bliss MacDonald. Bliss, as he was always known, was born on the 11th May, 1924 at Bayside, and was the son of Herbert and Edith MacDonald later of Hardwicke, Co. Northumberland, New Brunswick.

The sad part of all this is the fact that on searching for Herbert Bliss MacDonald we

quickly found that he had joined the Canadian Army, was Killed in Action on the 27th July, 1944 and lay buried at Shorncliffe Military Cemetery, a mere stroll from where I

had been trained as a young police constable all those years ago. At that point the circumstances surrounding the death of my newly discovered father were unknown

and being realistic and being only too well aware of the fact that thousands of other young men had lost their lives during the D Day Invasion of Normandy, my hopes of ever knowing any more seemed to be too much to hope for.

The next task – to find my Canadian family

My next task was to contact my ‘new’ family in Canada. More research found that I still had an aunt, Mrs Marion Baxter who lived with her husband Charles in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Marion was the youngest child in the family and she was only ten when Bliss went off to war. As Marion is an elderly lady I decided to write to one of her daughters, Anne, explaining everything to her. I included all my family details and contacts in order that Anne could see that this was a genuine approach to them. In the letter to Anne I also enclosed a letter to her mother Marion. I had no idea as to the state of Marion’s health nor indeed how she would react to such news for ‘Aunt’ Marion was well into her eighties. Subsequent correspondence showed that I really need not have worried about that!

A very considerable time went by and I had heard nothing from Anne. I had almost given up hope when I received an email from her on the 25th November, 2019 telling me that she had just arrived home for lunch and there was my letter. She had immediately contacted her mother and was going to see her that weekend in Halifax.

The response from Anne was so warm and welcoming and this has been the case from all members of the family ever since. I could never have hoped that this would be the reaction from this new and unknown family and to say that I felt grateful and emotional is putting it mildly. I so well remember sitting in our dining room, with Cheryl holding my hand and reading Anne’s email with tears running down my face; a truly emotional an unforgettable moment in my life. After all those long years not only did I know who my father was but I now knew that I had already been accepted and welcomed by his family in Canada.

27th July 2019 – We visit my father’s grave at Shorncliffe

On the 27th July, 2019 Cheryl and I, together with our children, Lisa, Stephen and Rachel and with our granddaughter Charlotte visited my father’s grave at Shorncliffe Military Cemetery for the first time. As one might imagine this was a visit full of emotion for all of us. There is little doubt that this was the first visit to Bliss’ grave by a relative since he was laid to rest in 1944. To mark the occasion we placed flowers on his grave and I recited a poem written by a very dear friend, the late Southampton Police Constable ‘Bob’ Smith. It says everything about soldiers buried ‘in foreign soil’. It was my way of paying tribute to my father who was Killed in Action at the age of twenty years so very far from home and family.

Getting to know my new Canadian family

During the following months I received many family photographs as well as a Christmas card written to Bliss by his mother and one from him to her. Of these treasured items, the most important of all were Bliss’ War Medals. Parting with those precious items showed just how much this new relationship meant to them. The medals arrived in their tiny original cardboard boxes, still wrapped in tissue paper. If anything showed that I had truly been accepted into the family then this was it. Here were my father’s medals and the family obviously thought that the proper place for them to be were with me, his son, a son that he never knew.

In the meantime Aunt Marion (she doesn’t like being called ‘aunt’ as it makes her feel old) took her own Ancestry DNA test. The result of that test was very significant indeed for suddenly Marion Baxter appeared at the top of my DNA list and was so much stronger a relationship than even my first cousin Ann and her daughter Jane.

The fact that I also appeared on Marion’s DNA list said it all for here was indisputable proof as to exactly who I was. That ‘hole’ in my life had now been well and truly filled for ever and I had the scientific evidence to prove it.

Having established that relationship I had to move on and find as much as I could about Private G45088 Herbert Bliss MacDonald of the Royal Canadian Ordnance Corps. Bliss, as he was always known, was born on the 11th May, 1922 in Hardwicke, Co. Northumberland, New Brunswick to Herbert and Edith MacDonald.

His father Herbert had served with the Canadian Army in France with the Royal Canadian Horse Artillery so here was a man who knew exactly what war was all about and the horrors associated with it.

I found that Bliss had left college and enlisted in the Canadian Army as a Volunteer on the 15th April, 1941. On that date he was still sixteen years of age. On volunteering he lied and gave his age as eighteen and his date of birth as 11th May, 1920. He gave his occupation as that of labourer but coming straight from college and never having had a job he could hardly describe himself as anything else.

The minimum age for enlistment/volunteering was eighteen but Bliss was certainly not alone in joining up before his time. Numerous family photographs show him in his rather ill-fitting BDs, (Battle dress) posing proudly with his mother and father and other members of this tight-knit family.

One must assume that his joining up had the Blessing of his father and mother but can one detect more than just a trace of sadness in their faces? Their youngest son was leaving home at sixteen to go off to war and they well knew that there was a very good chance that they would never see him again. Canadians by their thousands answered the call to arms and volunteered to serve King and Country and the Empire; Private Herbert Bliss MacDonald wanted to make sure that he was one of them.

Off to War

On the 16th September, 1941 Bliss found himself on a troop ship heading for Scotland, a very dangerous and uncomfortable voyage across the North Atlantic arriving on the 29th September. According to his records Bliss was admitted to Military Hospitals, including one in Edinburgh, shortly after disembarking from the ship and he remained there until February, 1942. I have been unable to find the reason for his hospitalisation.

Having been discharged from hospital he was posted to his new job in the Royal Canadian Ordnance Corps with the Vehicle Inspectorate. It would appear that he was posted to Bordon, Hampshire and from there he would travel quite extensively across the country. Fifteen years’ later I would find myself living in Bordon with my family when my step-father was posted there as a Gun Fitter/ Instructor.

Canadian Army Records provide a vital clue

I was very fortunate indeed in having access to all of my father’s Military Records, right from the day that he joined until the day that he was Killed in Action and the legal documents for his poor mother to complete. So much information and all available on line.

At the very bottom of the very last page, written very small indeed were the words that would eventually lead me to discovering how my father died. It said, ‘#3 Det (Tin Hats) 15 Cdn Aux Serv. Sec. Type K T.O.S. from 4 List R.C.E.M.E Embarked in UK. 24 July – missing from enemy action en route to France S.O.S. X6 R.C.E.M.E. List

Date of Casualty 27 July 44 # Id 27 August 44

Bliss had been posted to the Tin Hats’ as the Commanding Officer’s driver. Sadly he was Killed in Action on the way to France by enemy action. That I could obviously understand, but who or what were the ‘Tin Hats’? He had been detached to the Royal Canadian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers (CRÈME) and the Canadian Army Auxiliary Service and that was all that I knew. I did not know how he had died and I certainly thought that I had come to the end of my search: how wrong I was.

Ruth Stanley

Author of A Different Type of Bombshell – The story of the Tin Hats’ journey through World War 11

I searched for ‘Tin Hats’ and apart from finding just how many people had Tin Hats for sale I really wasn’t getting very far until I came across Ruth’s name and the fact that she was in the process of writing an historical and very personal account of the Canadian Tin Hats and their part in entertaining Canadian troops during the war. They were, in fact, a very professional and talented ‘Concert Party’, all of whom were fully trained Canadian Army soldiers. Ruth’s father, Private ‘Bill’ Dunstan was one of them and was ‘volunteered’ with another member of the company to become a female impersonator. Bill was very good looking man who spent much of his time explaining that he had not volunteered for the role. Be that as it may Bill was very good at it. Having female impersonators in the British Army goes back many generations and there was an obvious need to fulfil the role as women were not allowed within the ranks.

Having made contact with Ruth it did not take long for her to impart the sad news as to how my father had met his death on the 27th July, 1944 whilst en route to France in the Steam Ship Empire Beatrice. The ship was attacked by a German E-Boat, what we would know as an MTB (Motor Torpedo Boat) whilst off the coast of Dover. A torpedo slammed into the side of the Empire Beatrice, tore off her stern as well as badly damaging the engines. In spite of that catastrophic damage the Empire Beatrice did not sink although everyone on board thought that she must and they quite rightly abandoned ship. The ‘Beatrice’ was not ready to die and she drifted down the Channel and went aground at Dungeness . From there she was recovered, had temporary repairs made and was taken to the Port of London. From there and after undergoing more substantial repairs she was towed to Scotland and had new engines installed and a new stern fitted. The ‘Beatrice’ was ready to fight another day but that is another story.

Lest We Forget

During that attack four members of the Tin Hats’ lost their lives as well as seven members of the crew. Their names were:- Sgt. Charles More; Gunner ‘Bert’ Witherall; Gunner Joseph RENNEY and Private Herbert Bliss MacDonald.

The crew of the S.S. Empire Beatrice who died were Able Seaman (A.B.) Norman Butler Baker 20 yrs; A.B. Svend Christensen 27 yrs.; A.B. John Grocott 19 yrs; A.B. Knud Erik Hansen 23 yrs; A.B. Bjorn Vlademar Madsen 21 yrs; A.B. William James Price 22 yrs; A.B. Aage Rasmussen 22 yrs.

I know that the bodies Gunner Joseph Renney, Sgt More and my father, ‘Bliss’ MacDonald were recovered from the sea near Folkestone by members of the Warwickshire Regiment who were stationed at Folkestone. They would have been taken to Shorncliffe Military Hospital and were buried a short while later. That did not include Gunner Witherall who for some reason was taken to France and buried at the Bayeux Military Cemetery.

I found that the stern of the Empire Beatrice is marked as a ship wreck and is used by diving clubs for their dives. A list of those who were killed in the attack contained only the names of the crew. An approach to a very interested dive manager ensured that the names of the Tin Hats’ who died are now included in that sad list.

Torpedo Tragedy by Ruth Stanley

I will leave Ruth to tell the story of the attack which was told to her by her father.

There can be but a few accounts of persons being on board a ship when a torpedo struck but this is one of them. Ruth’s father Bill recounted the story to Ruth and that account and some of the details of the Tin Hats’ certainly deserves to be included in this story for it very much their story as well and for that I am very much in their debt.

The Canadians participated in the D-Day invasion on the beaches of Normandy at Saint-Aubin-Sur-Mer. By July 10, they had reached Caen in northwest France and by August 25 had participated in the liberation of Paris. The Tin Hats were scheduled to join the Canadian Army in France. Twenty members of The Tin Hats set off for France just after D-Day including Corporal Wally Brenan, Private Harold Buskirk, Private AJ Cormier, Acting Corporal John Rocks, Gunner Joe Renney, Acting Sergeant Charles More, Private Norman Harper, Private Frank Miskelly, Tapper J. Bendit, Private Herbert “Bliss” MacDonald, Gunner Albert Witherall, Private Johnny Heawood, Private Bill Dunstan, Private Harry Elsdon and Private Jack Phillips.

The men boarded the SS Empire Beatrice on July 24, 1944, waiting in the Thames for a convoy to take them over to Normandy. During their wait, The Tin Hats had undergone lifeboat and other drills in case of trouble. The ship finally sailed late on July 26 for France. Unfortunately, the voyage was not to be a pleasure cruise. Close to midnight and halfway across the Channel, the crew and passengers could hear gunfire from one of the navy escort boats but failed to hear the German E-boat warning. Acting Corporal John Rocks heard the alarm and hastened to advise the rest of the Concert Party to stand by the side of the ship. He may not have gotten to everyone in time. The torpedo hit the ship in the stern just behind the men’s quarters just off the coast of Dover, but the ship did not sink. The stairways from the hold deck collapsed and some of the entertainers fell through but managed to get safely back on deck. When the floor gave way, some of The Tin Hats were left hanging by their hands and one of the men was buried under some rubble at the bottom, before being rescued by his fellows. I can imagine a chaotic scene that involves all of my senses. There is an ear-splitting explosion. I hear people shouting, calling out to each other, grunting to pull people out of the ship’s hold and the slap-slap of their feet as they run in a desperate search to find their comrades. I feel the shuddering impact of the torpedo and the adrenaline coursing through my veins. I smell the acrid sting of explosives and burnt wood, the heat of the explosion and the tang of blood. I taste the mounting fear. I see people’s injuries. I feel a sense of rising panic and I clench my teeth against a sudden sense of loss and desperation.

The members of The Tin Hats would have felt all of this and more during this incident. They may have seen some horrific things during their travels in Italy, but this would have been the first time that they were physically impacted by enemy action. In typical fashion, all my father said to me about this incident was, “We were torpedoed just off the coast of Dover. I didn’t like that too much, I scraped my hands.” In interviews, he did, however, describe the moment that the torpedo hit. Fearful of what might happen during the dangerous crossing, my father was unable to sleep. He was settling down to sleep, when the alarm sounded at 2:30 am. According to my father, the torpedo bounced him out of bed.

The Concert Party members were able to get into some lifeboats although they were very crowded. With Johnny Heawood and Harry Elsdon, my father headed for a lifeboat, which stuck half-way down. Another was swinging clear and they held the ropes while the soldiers and crew carefully made their way down into the lifeboat. My father described his flight into the lifeboat. He was coming carefully down the rope hand-over-hand when someone called up that the lifeboat was full. In a panic, he slid some twenty feet into the boat, skinning his hands in the process. The boat was overcrowded and was taking on water. Ever resourceful, the entertainers found a way to keep the boat afloat. Frank Miskelly found a boat pump and, despite a crushed foot, began to pump out the water. Jack Phillips used a stiletto he had collected in Italy to cut a bucket free and began to bail as well. Another man, not finding an oar lock, used his leg as a lever to row the lifeboat. After the shouting and confusion aboard the SS Empress Beatrice, the silence on the lifeboat would have been welcome, each man absorbing the shock or doggedly doing what he could to keep the lifeboat going. All were relieved when a naval boat arrived, as they were not confident that the lifeboat could keep afloat for long. The survivors did manage to reach shore, only just, as one of them was taking on water and had to be bailed by hand. In the confusion, some members were taken back to Dover and others to the coast of France. Interestingly, the rescue party found them singing to while away the hours until they were found. The five or six of whom were injured were taken to Dover County Hospital and the remainder went to the 2nd Battalion 7th Royal Warwicks at the South Front Barracks for breakfast, bath and bed.

Those of the party that landed at Folkestone joined them later. In the confusion, newspaper reports were sensational. Time Magazine reported that ten members of The Tin Hats had died, that seven others sustained significant injuries, that their Director lost a leg and that it took some time for the unit to regroup. My father maintained that only five members of the Concert Party died. A clearer picture of the tragedy began to emerge. Four soldiers associated with The Tin Hats were confirmed “lost at sea”. The tragedy struck a chord with the Canadian public and newspapers began to provide more detail about the individual members of The Tin Hats, both missing and injured. Sergeant Charles More, Band leader from Toronto, had been one of the original members of The Tin Hats back in 1941. Before joining the Army, he had played the trumpet with Luigi Romanelli and other famous bands. Private Joe Renney, the stage manager from Vancouver, originally joined The Tin Hats as a conjurer, his peace time occupation. He later became their stage manager. Private Bert Witherall, a trombonist from Kingston, joined The Tin Hats shortly after their debut. He had been a trombonist for twenty-three years in the Army, playing with the Queen’s Bays and the Royal Canadian Horse Artillery. Private Bliss MacDonald, a Maritimer, was their driver. Private Harold Van Buskirk, a former department store clerk who was well-known for his singing, acting and dancing at the Vancouver Playhouse and Little Theatre groups, was wounded. In addition, Private Albert “Peewee” Beaudouin had a minor arm injury, Private Norman Harper broke his arm and Private Frank Miskelly crushed his leg. Adding to this misfortune, the orchestra’s instruments were also lost in the incident. The Tin Hats were to have been among the first educators, but this tragedy delayed their arrival on the Continent for the front-line circuit.

They performed again on August 14, 1944 in Aldershot with the remaining members of the original unit. The show had to be re-organized to cover for those who were missing. Slowly picking up the pieces, the Concert Party brought some new members into the show. It was through this tragedy that Canadian audiences got to know more about the individual members of the cast. By the time they began to tour Canada, they were well known by the audiences.

In Memoriam Sergeant Charles More, a member of the Auxiliary Services, was buried at the Shorncliffe Military Cemetery in Folkstone. He was 41 years old. His wife, Mary Beatrice More, continued to live in Uxbridge, Ontario. Gunner Albert Witherall, a member of the Royal Canadian Artillery, was buried in the Bayeux Memorial in Calvados, France as some of the survivors of the torpedo attack were mistakenly taken to France. It may be that he died en route. He was 41 years old and the son of Mrs. A Witherall of Kensington, London. Private Joseph Renney from Vancouver does not appear to have been buried at either of these cemeteries. As the ship did not sink and was recovered, it is unlikely that he was killed on board. He was listed as lost at sea and may have been pitched overboard in the explosion. Sadly, his wife and children were kicked out of their apartment once it was discovered that he was missing. As Mrs. Renney had to return to her parents, it is possible that without a body, it took time for his wife to access a pension.

I did look up Private Joseph Renney in the archives, but did not see his name in the casualties list, so perhaps his death remains unsolved. The only casualty that I was able to find around July, 1944 was that of Joseph Leo Rennie who died on August 22, 1944. His parents were, however, from Antigonish, New Brunswick and he was unmarried.

Through a happy coincidence, I came to know more about Herbert “Bliss” MacDonald. His son, Paul Donnellan, noticed my blogs about The Tin Hats and reached out to me from England to share information about his newly found father. He has graciously allowed me to include pictures of Bliss MacDonald and glean information from his father’s military records. Bliss MacDonald was the driver for the Commanding Officer of The Tin Hats and only 20 when he joined the Concert Party.

A Maritimer from a family with a proud military history, he enlisted at sixteen in Moncton, New Brunswick. He was posted to the Royal Canadian Ordnance Corps and was in England by 1941. Interestingly, one of his first assignments was with the Mobile Laundry Service. After undergoing driver training, he spent time in the Motor Vehicle Inspectorate. Although much of his service was in Brighton from 1941 to 1944, he spent quite a lot of this time in various Canadian General Hospitals for unknown reasons. Shortly before leaving for France he was transferred to the Royal Canadian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers (RCEME) and posted to No. 3 Detachment (The Tin Hats) of the Canadian Army Show on July 20, 1944. Bliss MacDonald died on the July 27, 1944, in what was described by his Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Hayes, as an ‘unfortunate incident’ while en route from England to France.

Bliss’ body was recovered from the sea by the 9th Battalion, Worcestershire Regiment, taken to the Military Hospital at Shorncliffe and was buried at the Shorncliffe Military Cemetery in Folkestone, Kent. As there are a large number of Canadians from the Great War buried there, he was in good company.

Bliss Macdonald received five medals posthumously. 1939-45 Star, for six months service on active operations between 1939 and 1944; • Defence Medal, for service in the forces in non-operational areas subjected to air attack or closely threatened, providing such service lasted for three or more years; • Canadian Volunteer Service Medal, for those who voluntarily served on Active Service and honourably completed eighteen months total voluntary service from 1941 to 1944; • War Medal 1939-45, for full-time personnel of the Armed Forces and Merchant Marines for serving 1941 and 1944; and • France and Germany Star, for one day or more of service in France, Belgium, Holland or Germany. Interestingly, crossing the Chanel en route to France, qualified Bliss for that medal.

My thanks to Ruth for allowing me to use that information. Ruth is a very kind an very helpful person and we correspond frequently.

Ruth has mentioned that she was unable to find any information regarding the fate of Gunner J. D. Renney. Although Ruth used the spelling of his name ending in ‘ie (now corrected to avoid confusion)’ she did try RENNEY, as indeed did I but without success. It wasn’t until a few days’ before my second visit to Shorncliffe that he appeared on the records as having been buried there. I was more that pleased to find Joe’s grave and leave a floral tribute for him.

The photograph below is of the Empire Beatrice taken after the war when she was purchased from H.M. Government and became the Mary K.

Lives Cut Short, But Not Forgotten by Ruth Stanley

Sadly, Bliss MacDonald left a baby behind. His son, Paul Donnellan, spent 76 years trying to locate his father only to find that he was buried across the road from the Shorncliffe Barracks, Sandgate where he trained as a policeman from 1962 to 1963. Below is a picture of Paul Donnellan aged 18 years, at the District Police Training Centre at Sandgate, Kent, taken in October 1962 just a short distance from his father’s grave. In a sad coincidence, he had no idea that his father was buried there. Paul Donnellan and his family visited Bliss MacDonald’s grave on 27th July 2020, on the anniversary of his death. Paul and his family, three generations in all, met at his father’s graveside and Paul read a poem penned by his late friend Bob Smith about a soldier boy asking if anyone remembers him. This was the first visit to the grave by family in 76 years.

Father and Son

Paul has told me that this private commemorative ceremony was a very emotional moment for them all. Somehow it seemed fitting that Bliss MacDonald would be laid to rest in such a beautiful and peaceful place overlooking the English Channel where Bliss and his friends died. The Soldier Boy Poem was written by a dear friend and colleague, Bob Smith. It is shared with the permission of the Smith family. Paul and his family have since placed a memorial brick for his father on the Normandy Memorial Wall at the D-Day Museum in Southsea, Portsmouth. Paul describes the ceremony below:-

The placing of the Memorial Brick was followed in November, 2021 when together with our Branch Chaplain and members of the Portsmouth and South East Hampshire Branch of the National Association of Retired Police Officers we held a Service at the D Day Museum. This Service was to remember relatives and friends of the family of the Hampshire Constabulary who had died as well as those who had served in the D Day Invasion.

Our chaplain, the Rev’d Sylvia Martin, Blessed the Memorial Bricks on the wall and included all who had served in that Blessing. As it was my very first Police Inspector, James Cramer had a newly installed Memorial Brick blessed. Also Blessed was my very first Police Sgt., Sgt. Eddie Wallace. I joined their shift at Portsmouth Central Police Station a few weeks’ after my 19th birthday. Inspector Cramer was with the Ulster Rifles – 6 Airborne and Sgt Wallace was with the Royal Artillery. The D Day Museum is located in the area covered by my first station. With my first Police Inspector and first Police Sergeant remembered on the Remembrance Wall, Bliss is certainly in the company of two very fine policemen and soldiers and that is something that is very special to me. I thought the world of them both for they taught this young ‘wet behind the ears’ policeman so many lessons, lessons about policing and most importantly lessons about standards in life. I try to forget the fact that I was frightened to death of both of them at the time!

Canada Day 1st July, 2022 – A very special day indeed

This has been quite a remarkable journey and on the 1st July 2022 I went with Cheryl to visit my father’s grave on Canada Day. I had heard that this was a very special day indeed for the people living in and around Sandgate and Folkestone for this is the day when the Canadian War Dead are honoured by the Mayor of Folkestone, the Chairman of Folkestone and Hythe District Council, The Royal British Legion, representatives of the Canadian military as well as other organisations and not forgetting scores of school children who come to place floral tributes on the graves of Canadian soldiers. They have been doing this since 1917 when the majority of those buried there were brought back from the trenches in France but who unfortunately died in Shorncliffe Military Hospital. It goes without saying that there are a few from the Second World War including my father Bliss and his two colleagues Gunner Joe Renney and Sgt.Charles More.

We were determined to attend but had great difficulty in finding out exactly what the arrangements were. I eventually managed to find Cllr. Tim Prater and asked for his advice. On learning of our ‘mission’ Tim invited us to call at his office and he would take us to the ceremony; how kind was that? We arrived on a blustery but beautiful day only to be met by several people who had heard our story via Tim and who wished to meet us. We met Tim’s Council Clerk, Gaye and later Amanda Plankenhorn and they really could not be more helpful and understanding. We made our way to the cemetery with the Civic Procession. A few yards into the cemetery and we were regaled by the beautiful sight of the cemetery and the English Channel in the distance. The cemetery is in a steep valley and we were able to look down and see the flags of the various organisations blowing in the breeze. Children were sitting down at their allocated graves in school uniform and it really was a sight to behold.

An impressive and moving Remembrance Ceremony took place including the sounding of the Last Post, the laying of Poppy Wreaths and the sight of the children laying their floral tributes was most touching. To think tht local school children have been doing this for over one hundred years says so much.

Immediately after the ceremony Cheryl and I found ourselves surrounded by Canadian military men and women and we both found that to be so very touching indeed. They stood at my father’s graveside with us to pay tribute to him and to have our photographs taken. All in all a most moving and unforgettable occasion.

Our next task was to locate the graves of Joe Renney and Charles More. There are an awful lot of graves to examine at Shorncliffe but thanks to the sharp eyes of Tim Prater who found both of them, we were able to lay our floral tributes; a perfect end to a day that we will never forget.

I hope that I am correct by expressing this thought but I must say that having the son of one of the many soldiers buried there to pay tribute to his father may have made the whole sacred exercise perhaps even more relevant to some. We could tell that the Canadians who were in attendance most definitely thought so. I most sincerely thank those who have tended Bliss’ grave and so many other Canadian graves for so long for it is heart warming to know that their sacrifice is neither forgotten nor taken for granted. I know that my ‘new’ Canadian family have the same thoughts.

To put some of this story into perspective I need to say that nearly half a million Canadians answered the call to arms and served in Great Britain during the war. Their role here was to protect us against an expected German invasion and year after year this must have been rather tedious; training, training and more training and not much else. For those Canadian boys their days of ‘Glory’ were to come on D Day when suddenly temporary camps all over the country were emptied of troops to take part in the greatest invasion of all time. So many of them never came back for they died on those beaches in Normandy and so many others were injured both physically and mentally. I used the word ‘Glory’ but my first Police Sergeant, Sgt Eddie Wallace, a D Day Veteran himself, once told me that there is nothing Glorious about being dead. Eddie was so very, very right in expressing that sentiment for he had been there and certainly knew just how ‘Glorious’ it all was.

As a newly promoted young Police Sergeant in 1973 I was posted to Portswood Police Station in Southampton. I spent four very busy and at times exciting years there and it was there that I met Police Constable Robert ‘Bob’ Smith. Bob was an extraordinary policeman in so many ways and perhaps many would describe him as a typical ‘bobby’ on the beat and yet he was far more than that. I would describe him as the sort of policeman that the public still yearn to see walking the beat and keeping them safe. He was wise, he was strong in personality and wisdom and he was frightened of no one. He also possessed a wonderful sense of humour. He was a true friend to the good people who lived on his beat and was feared by those who failed to obey the law. I thought the world of him but what I didn’t know about him was that he was an author and poet. At his funeral I saw that he had written a poem , The Soldier Boy which touched my heart. This is the poem that I recited over my father’s grave. Although Bliss was not English he was certainly Canadian and very British and the words of that poem apply to him as well as many thousands of our War Dead, buried as they are in ‘foreign soil’. It is a tribute to all of them and in particular four young soldiers of the Tin Hats and the young crew of the Empire Beatrice and that is why I have included it here.

The Soldier Boy

by former Southampton Police Constable Robert Smith

Oh give me a village in England

That basks in the warm summer sun

And give me the peace of an English field

When the harvest is all done

And the sound of distant church bells

As they ring our on high

And the sight of an English skylark

That wheals and dives in the sky.

Oh grant my spirit the power

To fly far over the sea

And to land on the wings of a butterfly

In the gentle summer breeze.

As I fly over hill and valley

With longing I glance below

And I see the smiling faces

Of the friends I used to know.

And if I could descend among them

And if they had the power to see

How many would rush to greet me?

How many would remember me?

For there is the inn where we gathered

Where the creamy froth stands on the beer

And there is the one who once loved me

Now another calls her ‘dear’.

But it is no use to remain any longer

For it grows dark at the end of the day

And my spirit is growing restless

It is time to be away

And though I would like to tarry

Yet I know it is all in vain

For I lie cold and still in the foreign soil

Now removed from suffering and pain.

And my message to you in my country

From those who answered the call

Remember, oh remember and do not forget

Those of us who for you gave our all.

If I ever thought that I was the only child left behind by a Canadian soldier father then I was well and truly mistaken for it is estimated that there were something in the region of 23,000 like me. The years have taken their toll and sadly some of those ‘children’ are no longer with us and others are still searching for their fathers to this very day. I can only empathise with them but they must never give up for the reward in achieving that goal is far too important and worthwhile. Believe me when I say that if they are successful it will change their lives forever.

Our next stage of this journey will take us to Canada to meet with our family this month (July 2022) and that really will be bringing closure to this search that has lasted seventy eight long years.

My most sincere thanks again to my dear friend Ruth Stanley and for her book, A Different Type of Bombshell which I will always treasure. The love, hard work and talent that Ruth put into her book in memory of her dear dad has been so worthwhile and she has secured the Tin Hats’ rightful place in the history of the Canadian Forces. Without Ruth’s help so much of this would never be known. When Ruth had finished writing her book she asked me to write the Forward to it. This was a great honour indeed and though I must say that it caused me several sleepless nights thinking about it I was more than happy to oblige.

My Mother and Father

It goes without saying that I owe so much to my wife, Cheryl and our children, Lisa, Stephen and Rachel without whose help, love, support and patience I would never have discovered who I am nor indeed, and to be candid, who they are. At this late stage of my life and at seventy eight years’ of age, that ‘hole’ in my life has at last been filled and I have a sense of peace within that I have never really known. It will come as no surprise when I say it is a truly wonderful feeling!

The End

Paul Donnellan

(Son of a Tin Hat) July 2022